The Authorship of The Night Before Christmas

By Seth Kaller

Though long acknowledged as the author of A Visit from St. Nicholas (The Night Before Christmas), author Clement C. Moore’s claim to immortality has been questioned by partisans who believe that Henry Livingston, Jr. should be credited for the classic Christmas verse. A careful look at the evidence clearly supports Moore’s authorship, and completely discredits the Livingston camp.

Note that Seth Kaller formerly owned the only Moore manuscript of A Visit which is now in private hands (three other Moore manuscripts are in museums).

Chapter I. A Brief Biography of Clement Clarke Moore

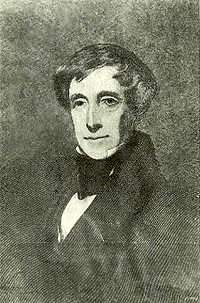

Clement Clarke Moore (1779-1863) was the only child of Benjamin Moore, an Episcopalian minister and rector of Trinity Church in New York City. (The elder Moore would go on to become the Episcopal bishop of New York and president of Columbia College.) His mother, Charity Clarke, was a feisty American patriot. From his mother’s side of the family, Moore inherited the farmland that would, during his lifetime, become New York City’s Chelsea district.

Moore did not follow his father into the ministry. Instead, after his 1798 graduation from Columbia College, he devoted himself to biblical and classical studies, with a focus on ancient languages. Moore’s two-volume Compendious Lexicon of the Hebrew Language, published in 1809, stands as a remarkable achievement and a symbol of his commitment to the beginning student of Hebrew, to whom it is addressed. It was a standard text in the field for many years. In 1818, Moore donated a large tract of land for the re-establishment of the General Theological Seminary, a New York City school for Episcopal clergyman. He served there as a professor of Oriental and Greek literature from 1821 to 1850. During that period, Moore wrote A Visit From St. Nicholas (1822), which he later published under his name in the volume Poems (1844).

According to extant archival evidence, Moore had a vibrant domestic life. He was devoted to his wife, Catherine Elizabeth Taylor, whom he married in 1813. (During their courtship, the smitten scholar composed poems to Catherine, and carved her name on trees.) When she died in 1830, not long after her thirtieth birthday, Moore wrote a devastating poem of bereavement (“To Southey” in Poems). Moore was left with seven children (two had died young) between the ages of three and fifteen. He never remarried, taking on the responsibility of the children’s education and upbringing. One of Moore’s sons, who apparently suffered from a mental disorder, remained at home under his father’s care throughout his life. Moore often wrote poetry for his children and grandchildren.

Clement Clarke Moore was a complex man whose life is best assessed within the context of his own era. Socially conservative, he was an ardent defender of property rights and a strong believer in personal responsibility. While critical of superficial pretense and “fashionable” behavior, he also firmly believed in tolerance and goodwill. The philanthropic Moore gave imaginative service to his community, personally underwriting the debts of Saint Peter’s Church (at an eventual, tremendous loss of $25,000), providing the church with an organ, initiating and teaching for over ten years at a free adult education program, and serving for forty-five years as trustee at Columbia. An erudite professor of theology and “dead” languages, he also loved music, theater and writing poetry for his grandchildren. Though Moore’s 1822 Christmas poem is, in many ways, uniquely reflective of his own period, its appeal has transcended time and place, serving as the basis of our modern-day Christmas rituals. Through Clement Clarke Moore, we continue to celebrate the spirit of love, goodwill, humor and tranquility of the family at home on Christmas Eve.

Chapter II. The Moore Things Change…

(from the Winter 2004 issue of the New-York Journal of American History.)

Let each one enjoy, with content, his own pleasure,

Nor attempt, by himself, other people to measure. – Clement C. Moore, “The Pig and the Rooster.”

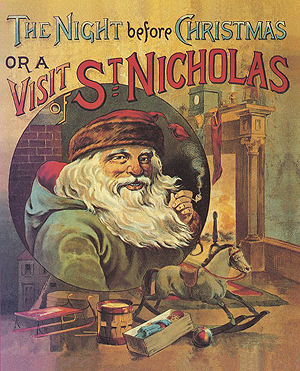

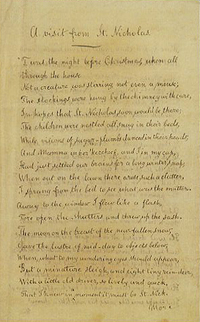

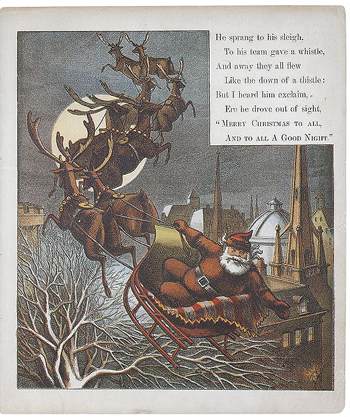

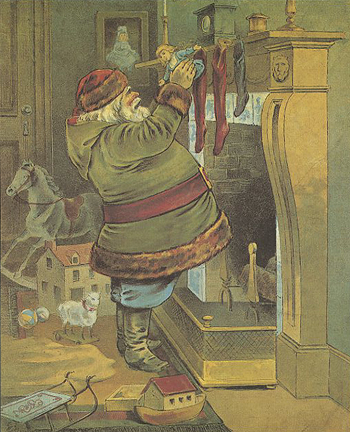

In December of 1823, A Visit from St. Nicholas, better known as The Night Before Christmas, was first printed, anonymously, in the Troy Sentinel. By the time Clement Clarke Moore included it in his own book of poems in 1844, the original publisher and at least seven others had already acknowledged his authorship. Four manuscripts penned by Moore, a biblical scholar, philanthropist and father of nine, survive: in The Strong Museum, The Huntington Library, The New-York Historical Society, and one in private hands. When the 83-year-old Moore penned The New-York Historical Society copy, he explained that he had originally composed the verse for his two daughters, using a “portly, rubicund Dutchman” in the neighborhood as his model for St. Nicholas (New-York Historical Society Quarterly Bulletin, January 1919, 111 and 114). Every piece of documentary evidence supports Moore’s authorship. But the facts have not prevented an attempt to turn history upside down.

Decades after Moore’s authorship had been confirmed, a member of the Poughkeepsie-based Livingston family “recalled” that, many years earlier, another family member had claimed that her father, Henry Livingston, had actually written the famous poem. There was no physical evidence. (A single manuscript copy was later said to have been destroyed in a fire.) Still, the clan began a campaign to re-attribute A Visit to the family patriarch. The date attributed to the first reading gradually shifted as details of the claims were discredited. (For instance, an ancestor who supposedly heard the poem read by Henry Livingston at Christmas in 1808, turned out to have died in August of that year.) After successive versions of the story were disproved, the Livingston camp eventually turned to ad hominem attacks. They argued that, unlike their beloved forbear, Moore couldn’t have written such a light-hearted, child-friendly poem, because he was a mean-spirited, curmudgeon, a hater of fun who despised rambunctious children.

Enter Vassar College Professor Don Foster and his book, Author Unknown: On the Trail of Anonymous (Holt, 2000). Foster admitted that much of the Livingston story had already been proven wrong. Even so, he claimed that linguistic forensics, his own foolproof method of detecting authorship, showed Livingston to be the true author. A reporter for the New York Times picked up Foster’s story, and called me for a reaction. Why me? I believe that A Visit is more than a relic of words on paper. This iconic poem created the modern vision of Santa Claus, a beautiful and captivating story at the center of holiday celebrations welcomed by Americans of every religion. When Moore’s only known privately-held manuscript had come up at auction in 1995, in partnership with my family and another manuscript dealer, I bought it. Having heard the argument denying Moore’s authorship, I replied that there are still people who don’t believe that Neil Armstrong walked on the moon. But, I thought, maybe this time, the accepted wisdom was wrong. So I read the book.

In Author Unknown, Foster repeats the old canard that Moore had been temperamentally incapable of writing the beloved poem. Moreover, he argues, it was stylistically implausible that the stodgy scholar had crafted such sprightly verse. Foster goes beyond prior attacks, claiming that physical evidence proves that Moore had appropriated another man’s work – and that it was not his first such offense. But, Foster’s reasoning is based on a series of flawed arguments, made even less credible by reliance on heavily-manipulated and selectively-used evidence. In the end, St. Nicholas, that “right jolly old elf,” is dragged headfirst down the chimney by a team of runaway fallacies. But with the help of The NYHS and the Museum of the City of New York, we can dust the soot off St. Nick – and Clement C. Moore.

Fallacy #1: Moore was already a plagiarist

Fact: The evidence used to support this assertion is false.

After too many recent reports, we’re ready to believe that plagiarism could be any author’s secret vice. In Author Unknown, Foster claims that in a book about Merino sheep, Moore had included “a handwritten note explaining how he happened to possess such a curious volume: he was himself the anonymous translator! …. he lays claim to an entire book that was the work of another man” (Foster 273-4). Then, voila!, Foster exposes the “fraud”: The last page of the book names the real translator (Foster 273-4).

Had Moore really tried to pirate another man’s work? I asked a research assistant to find the book. Luckily, it was easily accessible, having been given to The New-York Historical Society circa 1814. The text of the incriminating “handwritten note” turned out to be nothing more than a misleading allusion to the inscription “by Clement C Moore A.M.” And what about it being “in his own hand”? It is clearly not in Moore’s handwriting [see Appendix A for this and genuine Moore signatures]. The evidence indicates that the inscription is a clerical error, probably reflecting Moore’s gift of the book. In no way does it show any attempt at plagiarism.

Fallacy #2: Moore was a Grinch

Fact: Every argument marshaled to support this claim is false.

Foster depicts the scholar as a self-righteous, moralizing paragon of rectitude who we can’t wait to deflate. (Foster 227) Moore was incapable of writing this poem, Foster argues, because he was a rich, all-around nasty person, who hated noisy kids, and by the way, his sons were all philanderers. Moore was “a grouchy pedant, a student of ancient Hebrew who never had a day of fun in his life. In fact he was against it”(Foster 227).

Time and again Foster makes his case by misinterpreting, or altering, evidence. In one instance, Foster quotes from one of Moore’s letters to show that “his own mother thought of him as a ‘woman hater,’ a scholar like ‘the long-bearded Jew who […] could love nothing but musty black-leather books’ ” (Foster 247, ellipses Foster’s). But a closer look at the letter reveals the truth – the young professor was poking fun at himself while in the midst of courting his future wife (“my warm-hearted, sweet-tempered girl”).

[W]hat would you do if you could see me through such a magic glass as we read of in the Arabian nights entertainment? The woman hater, the long-bearded jew, who as you all supposed, or pretended to suppose could love nothing by musty black-letter books, is converted into as spruce & gallant a lady’s man as you ever beheld…we ramble about in the country and talk all manner of nonsense; I cut her name upon the trees and try, without success, to make verses….You have long predicted that I should sooner or later be brought to this….” (Moore to his mother, October 16, 1813, NYHS).

How could any objective observer not recognize that the phrase “pretended to suppose” (elided in Foster’s quote) is a clue that Moore is kidding?

But what about the child-hating, noise-obsessed Moore? A passage from an unpublished 1849 verse, written by the poet for his granddaughter, puts the lie to that characterization: “The house is all too dull and quiet;/ I long to hear you romp and riot/ When e’er you’re full of harmless fun,/I dearly love to see you run” (Misc. Moore, C.C. Coll. Museum of the City of New York).

Fallacy #3: Moore was a Scrooge

Fact: Moore celebrated Christmas and also wrote what is probably the first “letter” from Santa Claus.

Moore, Foster claims, disapproved of verse that was not spiritually useful and abhorred the veneration of saints – including St. Nicholas.“From Moore’s point of view,” states Foster, “Christmas was no time to be jolly, but a season for worship, for repentance from sin…. When the evidence is laid out on the table, one cannot help but wonder how “A Visit from St. Nicholas” ever came to be associated with an old curmudgeon like Clement Clarke Moore in the first place” (Foster 245; 266).

So was Moore indeed morally and constitutionally incapable of writing A Visit? Absolutely not. Proof positive is in the Museum of the City of New York, where we discovered a previously unknown Santa poem. It is written, without a doubt, in Moore’s handwriting. Based on content and the addressee, one of Moore’s daughters who was just learning to read, it probably predates A Visit by one year. In the form of a letter in verse (perhaps the first letter written by Santa Claus), it provides another major link in the story of the invention of the modern Santa.

Fallacy #4: Stylistic evidence proves that Henry Livingston wrote the poem

Fact: Even a scientist can be wrong, if he relies on tainted evidence. “Linguistic forensics,” if fairly employed, actually proves that Moore is the author.

Foster and the Livingston camp claim that a linguistic analysis of A Visit supports Livingston’s claim of authorship and opposes Moore’s. Are they right?

As Dr. Joe Nickell, author of Pen, Ink and Evidence, points out in his thorough analysis of Foster’s work, “[i]t is easy to fall into the trap of starting with the desired answer and working backward to the evidence, picking and choosing that which best fits” (Nickell,Manuscripts, Winter 2003, 10). That’s just what Foster does, using linguistic analysis selectively, and disregarding all evidence in favor of Moore’s authorship. Lighthearted, spontaneous-sounding mixed iambs and anapests, exclamation marks, the “rare” use of “all” as an adverb, syncopation, familial affection – the “evidence” for Livingston can also be seen in many lines written by Moore. And let’s not forget the language. When Foster discusses the origin of certain words or phrases from the poem (“all snug,” for example), he goes to tortuous lengths to create an association with Livingston, only to ignore much more direct connections to Moore. In any case, the circumstantial evidence that Foster cites to support his claim, even if it were true, would still prove nothing. Livingston might have been likelier to employ a particular word or style of punctuation, but this does not mean that Moore never did so. As already shown, there is both documentary and historical evidence supporting Moore; the same cannot be said for Livingston.

A broader analysis, however, yields more conclusive results. Foster and the Livingston family now claim that the poem was written by Henry Livingston circa 1808. But as shown in Stephen Nissenbaum’s 1997 book, The Battle For Christmas, the poem clearly reflects the later influence of Washington Irving, The New-York Historical Society and the Knickerbocker movement, once again pinning authorship to Moore. Contextual sources date the poem to 1822, consistent with all the other evidence that Moore penned the classic verse.

In the end, Foster bases a great deal of his claim on his high opinion of Henry Livingston, “an artist, journalist and poet… a free spirit and all-round merry old soul if ever there was one” (Foster 227). In today’s world, many would feel comfortable believing that we owe our much-loved “jolly old elf” of Christmas to a free spirit, not an earthbound pedant. But Moore’s creation is all the more moving, having arisen from the private heart and imagination of a publicly serious scholar.

Let’s give the final word to Mr. Moore, with an excerpt from a manuscript poem in the collection of The New-York Historical Society (Misc. MSS Moore C.C.). Likely written in 1813, on the occasion of his marriage to his beloved Catherine, Biography of the Heart of Clement C. Moore offers the poet’s clear-eyed assessment of his own character.

He shone not with the fire-fly’s light,

Which shows itself in flashes bright, But with the glow-worm’s steady ray The constant lustre of the day.

That steady ray still lights up the faces of children every year on Christmas Eve.

Chapter III. The Livingston Claim

The “Recovered” Memory

The Livingston claim is now based on the recollections of a relative, Eliza[beth] Clement Brewer Livingston. In 1848, 1861, or even later (no one in the family knows), Brewer read Moore’s poem and “recalled” that her father-in-law had written it 40 or 60 years earlier. Foster admits that “the external evidence for Harry Livingston’s authorship of the poem depended on the recollections and anecdotes of his children and grandchildren, who seem to have settled on Christmas morning 1808, at breakfast, as the occasion on which Major Henry introduced his family to ‘a right jolly old elf...’” (Foster 237).

Other evidence suggests that the family might have mistaken A Visit for a Christmas poem Livingston did write. The Livingston memories about that Christmas morning are admittedly vague: previously discredited family claims were equally certain that the poem was written between 1780-1800, or in December of 1805 or 1807. Even Brewer’s epiphany is hard to credit as a historical record: The date of her pronouncement was probably neither 1848 nor 1861; the 1863 Harper’s Weekly printing seems most likely, as the Thomas Nast drawing mentioned in family lore appeared in that issue. The written Livingston family claims begin around 1870, at which point the children and grandchildren started to compile and compare their memories by letter. In contrast to the moving target of Livingston camp claims, historical evidence proves that the poem was written in 1822, not before.

One Witness Dead, One Misplaced

Livingston family legend explaining how Moore “stole” Christmas is also easily proven wrong. The family now believes that after Livingston wrote the poem in December of 1808 (which is impossible, as we show elsewhere), he read it to his family and guests on Christmas day of that year. One guest, the story goes, took a copy and went directly to work for Moore as a governess. (Aha!) However, the family member credited with this memory, Catherine Livingston Breese, died on August 21, 1808 – four months before the event took place. Other facts get in the way, too: Moore was still a bachelor at that time; he had no need for a governess until 1815.

Publish or Perish

If Livingston wrote A Visit in 1808, why wasn’t it published earlier? He often submitted his poetry for publication, and wrote a regular New Year’s address that was printed in the Poughkeepsie paper. His descendants have spent more than 40 years trying, and failing, to find printed evidence to back up their claims. And why didn’t Livingston take credit for the poem during his lifetime? Between its first publication in 1823 and Livingston’s death in 1828, the poem was republished many times (see Appendix D). Why not correct the record? Moore, a serious scholar, had reasons to hesitate to claim authorship of a whimsical children’s poem. Livingston did not.

Chapter IV. Context and Content

Santa Claus Didn’t Come Out of Thin Air

A Visitresponded to cultural trends and concerns specific to 1820s New York City. As shown in Stephen Nissenbaum’s well-researched cultural history, The Battle For Christmas (1988), Moore was influenced by Washington Irving, John Pintard and Gulian Verplanck, and their association with The New-York Historical Society and the Knickerbocker movement.

Washington Irving’s History of New-York from the Beginning of the World to the End of the Dutch Dynasty by Dietrich Knickerbocker, originally published in 1809, was reprinted in 1821 with additions to the text. It is this latter edition that is acknowledged by Christmas scholars as an obvious source of the poem’s inspiration.

… the good St. Nicholas came riding over the tops of the trees, in that self same waggon wherein he brings his yearly presents to children. … And when St. Nicholas had smoked his pipe, he twisted it in his hatband, and laying his finger beside his nose, gave the astonished Van Kortlandt a very significant look; then mounting his waggon, he returned over the tree tops and disappeared (cited in Elliott 42).

St. Nicholas’s gesture of “laying his finger beside his nose,” one of the 1821 additions, was taken up by Moore in his Visit. This is an important piece of evidence supporting 1822 as the date that the poem was written, not earlier, as the Livingston claim alleges.

The Donder Party

Moore’s “Donder” and “Blitzen” are authentic German words for thunder and lightning. When Don Foster argues that Orville Holley, the poem’s original publisher, “got it right” by printing the reindeer names as “Dunder” and “Blixem” (the Old Dutch words for thunder and lightning), he overlooks the Knickerbocker pseudo-Dutch heritage movement, which could easily have induced an editor such as Holley to change German to Dutch or to “correct” a variant spelling. Moore’s own manuscript versions are consistent and he actually corrected “Blixem” to “Blitzen” in Tuttle’s broadside reprint (Museum of the City of New York, MS Col. Cab 2, Letters – Tuttle, 54.331.17A-B).

A Snug Case of Misinterpreted Evidence

What was the inspiration for the phrasing in A Visit? The following two passages provide a likely source for the memorable use of the word “snug” (“all snug in their beds”) in the Christmas poem. Both Sir Walter Scott and Washington Irving were authors known to Moore, and there is additional contextual evidence indicating that Moore had read Irving’s 1821 edition of Knickerbocker History before writing his poem.

“But you must remain snug at the Point of Warroch till I come to see you.” “The Point of Warroch?” said Hatteraick, his countenance again falling; “What, in the cave, I suppose? – I would rather it were any where else; – es spuckt da! – they say for certain that he walks – But,donner and blitzen! I never shunned him alive, and I won’t shun him dead.” [Sir Walter Scott, Guy Mannering, 1815]

Such at least was the case with the guileless government of the New Netherlands; which, like a worthy unsuspicious old burgher, quietly settled itself down into the city of New Amsterdam, as into a snug elbow chair – and fell into a comfortable nap – while in the mean time its cunning neighbours stepp’d in and picked its pockets. [“Diedrich Knickerbocker” (Washington Irving), A History of New York, from the Beginning of the World to the End of the Dutch Dynasty, 1809 and 1821]

Don Foster ignores those obvious links, instead choosing to interpret the word “snug” as a key Scottish-Irish link to Livingston (Foster 259-60), and offering this as further “proof” against Moore. But to do so, Foster has to overlook a mass of evidence in the Oxford English Dictionary (OED) and the Literature Online (LION) databases, the very sources which he consulted in performing his linguistic analysis.

Foster writes that the earliest recorded instance in OED of “snug” meaning “tidy” is Allan Ramsay’s Gentle Shepherd. “Great Scot!,” Foster adds, “Allan Ramsay was one of Henry Livingston’s favorite poets” (Foster 259). But in OED itself, Sir Richard Steele’s 1714 Lover is actually the earliest instance cited. A dozen other usages closer to that of A Visit are also ignored so Foster can claim that for “the earliest instance of ‘snug’ for cozy the OED cites Christopher Anstey,” a poet he can connect to Livingston. But the OED definition that cites Anstey is not the “snug” usage from the Christmas poem, as in “to lie snug in a Bed” (Miége, 1687), or even “snug” as in “comfortable and warm, cosy” (as in “snug warm bed,” in Beresford, 1806). Instead, Foster’s “earliest instance” cites “snug” as in:

Marked or characterized by ease or comfort; comfortable, cosy. (a) 1766 [ANSTEY] Bath Guide xiii. 16 No Lady in London is half so expert At a snug private Party, her Friends to divert.

On the other hand, Moore’s description of the “plump-visag’d, snug, and tidy wife” in his poem “A Trip to Saratoga” (Poems, 1844) seems not to have merited Foster’s attention.

Foster also claims that in LION the second earliest instance of “all snug” appears in John O’Keeffe’s 1789 comic opera, The Highland Reel. “That’s of interest as well,” he states. “[T]he two latest items in Henry Livingston’s music book (1776-1784) are from John O’Keeffe” (Foster 260). Actually, there are three recorded uses of this phrase pre-dating O’Keeffe. In any case, this is a specious argument. Hundreds of LION entries prove that “snug” was hardly a rare word and “all snug” had become a common-enough phrase for Moore to have written “all snug in their beds” in 1822 without any help from Ramsay, Anstey or O’Keeffe. This belies Foster’s assertion that both Livingston and the author of A Visit were “indebted, directly or indirectly, to the identical poets (including, I think, Allan Ramsay, Michael Drayton, Christopher Anstey, William King, John O’Keeffe, and Matthew Lewis, none of them poets who influenced Clement Moore)” (Foster 260).

That list also conveniently leaves out all of the writers from the first decades of the 1800s who used similar words or phrases, including Jane Austen, John Keats and two authors who undoubtedly did influence Moore: Sir Walter Scott and Washington Irving, as quoted above.

The Pipe is Not a Smoking Gun

The pipe in A Visit was not a pro-tobacco slip, as Don Foster argues, but rather “code” that everyone in 1822 New York would have understood. Moore’s St. Nick may have been a bishop, like the real saint, but the short pipe alone made him a working-class hero. Such imagery was a clever wink at Knickerbocker efforts to create a Christmas holiday for all classes.

Antecedent Anapests

Clearly, Moore, a Greek scholar, would have been well-versed in anapests (the rhythm used in A Visit) from his reading of Aristotle, and other classical, as well as contemporary, sources. It was by no means an uncommon form of verse. Moore’s poem “The Pig & The Rooster” (see Appendix B) an amusing anapestic verse about narrow-mindedness and tolerance, is another example of his use of this format.

Yet when Don Foster located two bawdy anapestic texts, he assumed that they must have been required reading for the author of A Visit, and then concluded that Moore would never have read them, or, if he had read them, would never have imitated the verses. Foster’s reasoning is doubly flawed. First, Foster focuses on other anapestic poems that did not served as Moore’s inspiration, while ignoring those that clearly did inspire the author. And second, the assessment of Moore’s taste in poetry, one of the strongest arguments the Livingstonians make to argue that Moore could not have written A Visit, does not hold up.

Tracking down the poet’s opinions on “anapestic satires” turns up John Duer’s A New Translation, With Notes, of The Third Satire of Juvenal, to which are added Miscellaneous Poems, Original and Translated (New York: E. Sargeant, 1806). According to Foster, in Moore’s preface to that book, he “condemned the ‘depraved taste in poetry’ of those who read anapestic satire, together with every ‘bawd of licentiousness” who writes it. Moore at age twenty-five fairly wept over the ‘influence which nonsensical and immodest verses may have upon the community’” (Foster 257).

But Foster’s pastiche of quotations bears no resemblance to its sources. Moore never comes close to mentioning the immorality of reading“anapestic satire” or “nonsensical and immodest verses,” as Foster states. In actuality, Moore’s attack is aimed at bad poetry, a polemic against the then-current fashion for maudlin sentimentality. Poets, he contends, should expend their talent on making some sense, rather than simply using sensational imagery and elaborate meter to disguise underlying vapidity. Moore then poses a rhetorical question: “[W]hy think so seriously of the influence which nonsensical and immodest verses may have upon the community, while there are already subjects of censure so much more important… than… a depraved taste in poetry?” He answers that bad taste leads not so much to moral, “but merely to intellectual depravity.” Shoddy verse is bad for poetry and for culture. As for the “bawd of licentiousness,” that phrase is actually taken from a quotation by Dr. Brown, who Moore cites in his discussion of links between popular culture and public education.

So did the scholarly Moore simply disapprove of light verse? Not at all. In his preface to the Juvenal translation, he did indeed write that “no production which assumes the guise of poetry ought to be tolerated, if it possess no other recommendation than the glow of its expressions and the tinkling of its syllables, or the wanton allurement of the ideas that it conveys.” But in the next sentence, he explained further.

It should be scrupulously required, that whenever words are put together, they be assembled for some rational purpose; that if the affections be addressed, the feeling intended to be excited be one of which human nature is susceptible; that if an image be presented to the imagination, its form be distinguishable; and that if reason be called upon, something be expressed which the mind can comprehend (xxv-xxvi).

Moore scrupulously followed this poetic program when he later composed The Night Before Christmas. There was a rational purpose to it: telling a story to entertain children, while providing (and inventing) a bit of history. The feelings he addressed were so “susceptible” to human nature, that almost 200 years later the verse is still read and loved. The images he presented were so “distinguishable” that they have inspired countless paintings, drawings and prints, and even other poetry and songs. One final, and I think telling, point on the subject: Foster’s footnote citing the Duer translation of Juvenal conveniently elides the word “Satire” from the book’s title.

Moore: The Mean, Rich, Dead, White Male Professor

We’ve already debunked the claim that Moore was constitutionally incapable of writing a light-hearted poem. That charge is, once again, based on flawed evidence. The writing samples that Foster uses to indict Moore and support Livingston are nowhere near comparable: Moore’s academic texts, professional letters and Poems vs. Livingston’s light verse (unpublished) and family letters. After all, Moore was writing as a father – not for publication, but for the entertainment of his children. Foster ignored all of Moore’s uncollected light verse, like the following undated “Saint Nicholas Poem” from the City Museum of New York’s archives:

What! My sweet little Sis, in bed all alone;

No light in your room! And your nursy too gone!

To support his claim that Moore was a moralizing old crank, Don Foster turns to the diary of George Templeton Strong. Based on passages from Strong, Foster depicts Moore as the tyrant of Saint Peter’s Church. Though Moore sponsored the organ and played it for services, Foster refuses to credit his generosity.

Some parishioners, though grateful, thought that the honor of playing [Moore’s donated organ] should have gone to Edward Hodges, a professional musician. George Strong remarks in his diary that the music thereafter was poor, for though the organ was ‘a very fine affair,’ arguably the best in the New World, ‘much can’t be expected from it when operated on by Clement C. Moore…a very scientific musician, but he’s sadly lacking in the mechanical department’ (cited in Foster, 244).

In fact, contrary to Foster’s observation, Strong’s entry doesn’t cite any controversy over who should be playing the organ. Strong, one of the most cultured music critics of his day, didn’t approve of Hodges either. When the latter obtained a post at Trinity Church, Strong acidly observed that “the [organ] music was generally ponderous, as under Hodges’s regimen one was prepared to find it” (Strong, Vol. 2, 278). What Foster fails to note is that, in his original remark, Strong referred to the author of A Visit as “my Clement C. Moore,” a phrase indicating a degree of affection, confirmed elsewhere.

In another excerpt from Strong’s diary, Foster simply identifies the wrong man. He writes that “Clement Clarke Moore, in the words of George Strong, was a man of ‘instinct with red, pepper, to a high degree of excitement’” (Foster 247). In their index, the editors of the Strong diary clearly identify the subject of this quotation as William Moore, not his father, Clement.

Despite his reputation as a sharp observer with a sharper tongue, Strong actually presents Moore in a positive light. Regarding Moore’s observation of his 1836 Columbia College final exams, Strong recalls: “It was horridly somniferous. How the conscientious Mr. Moore endured it I know not; he stuck by for three mortal hours,” while other trustees snored loudly in their seats or quietly snuck away (Strong, Vol. 1, 29). It also appears that Strong relied on Moore’s fair judgments and unbiased, progressive opinions when the two men served on the Columbia College Board of Trustees. (See the Strong Diary, Vol. 2, 143-246, for the Wolcott Gibbs controversy.)

Of course, fairness and conscientiousness do not necessarily go hand-in-hand with a sense of humor, and arguments have been made that Moore was dry and pedantic by nature. His many affectionate letters and verses to family and friends contradict this characterization. So too did his eulogists, who recalled him as a man of “quiet, sparkling humor,” “warm hearted in friendship, genial in society…and of cheerful humor” (Sonne 379).

Chapter V. Summary

Clement Clarke Moore, immortalized for writing The Night Before Christmas, has been unjustly accused of taking false credit for the classic holiday poem. But any unbiased look at the evidence – documentary, historical and linguistic – must lead to the conclusion that Moore was indeed the work’s author.

In Author Unknown, Don Foster concludes that “The words on the handwritten or printed page are more indelible than fingerprints, and more dependable, if carefully assessed, than eyewitness testimony” (Foster 282). But two years after publishing his indictment of Moore, Foster was forced to retract his own attribution of a funeral elegy to William Shakespeare. (Foster’s linguistic analysis of that elegy was highlighted in Chapter I of Author Unknown.) “[P]eople…often commit acts or write texts that you wouldn’t expect of them,” he acknowledged belatedly. “Personal opinions cannot stand for evidence, nor can personal rhetoric” (12 June 2002 Foster posting to shaksper.net).

I started this investigation with a willingness to let the chips fall where they may. In the end, I can conclude that when all the “personal opinions” and “personal rhetoric” are put aside, there is not a shred of real evidence to support the Henry Livingston case. He may have been a great guy, and he may have even written a Christmas poem, long forgotten, but he didn’t write this one. In terms of deconstructing the Livingston arguments put forth by Don Foster, the preceding text is just the tip of the iceberg – it would be too tedious to list here the many additional examples of factual errors and flawed logic. But if you ever find a different argument than the ones that I responded to above, drop me an email. I probably have more information on file.

My quest to find the truth behind the so-called Christmas controversy has given me a deeper look into the life and work of Clement C. Moore. A critical biography of the writer and scholar has not been written in almost fifty years, and many of his wonderful poems have yet to be published. In fact, because of this investigation, Moore’s verse “From Saint Nicholas” (which may very well be the earliest letter written by Santa Claus) appeared in print for the first time, in a New Yorker piece on Dr. Joe Nickell, one of the researchers who took an interest in this case. I am willing to bet that more will now be published about Moore, the indisputable author of America’s most beloved Christmas poem.

– S.K.

Research assistance provided by Cynthia Henthorn, Marilee Scott, Jeffrey Bolas and Ellen Pawelczak.

References

Anon. “Original Documents from the Archives of the Society: The Autograph Copy of the “Visit from St. Nicholas.”

New-York Historical Society Quarterly Bulletin. Vol. 2;4 (January 1919): 111-115.

Bilger, Burkhard. “Waiting for Ghosts. (Committee for the Scientific Investigation of Claims of the Paranormal Investigator

Joe Nickell).”New Yorker, 23 Dec 2002, 78(40):86+. Expanded Academic ASAP. infotrac.galegroup.com.

Benchley, Robert. “Books and Other Things.” New York World. Dec. 11, 1920.

Burrows, E. and Mike Wallace. Gotham: A History of NYC to 1898. New York: Oxford University Press, 1999.

Elliot, Jock. “‘A Ha! Chistmas’: An Exhibition at the Grolier Club of Jock Elliot’s Christmas Books.”

New York: The Grolier Club, 1999.

Foster, Donald. Author Unknown: On the Trail of Anonymous. New York: Henry Holt and Company, 2000.

Haight, Anne Lyon. Foreword. “The Night Before Christmas”: An Exhibition Catalogue. Ed. George H. M. Lawrence.

Pittsburgh, PA: The Pittsburgh Bibliophiles, 1964.

Hosking, Arthur Nicholas. The Night Before Christmas. The True Story of a Visit from St. Nicholas. With a Life of the Author,

Clement Clarke Moore. New York: n.p., 1934.

Jones, Charles W. “Knickerbocker Santa Claus.” New-York Historical Society Quarterly. Vol. 38 (Oct. 1954): 357-83.

Kirkpatrick, David D. “Whose Jolly Old Elf Is That, Anyway?” New York Times, October 26, 2000, E1.

L. [Clement Clarke Moore]. “A Letter to the Author from a Friend.” A New Translation, with Notes, of the Third Satire of Juvenal,

to which are Added, Miscellaneous Poems, Original and Translated. Trans. Anon. [Duer, John]. New York: E. Sargeant, 1806.

Literature Online (LION).

Lowe, James. “A Christmas to Remember: A Visit from St. Nicholas.” Autograph Collector. January 2000. 26-29.

MacCracken, Henry Noble. Blithe Dutchess: The Flowering of an American County from 1812. NY: Hastings House, 1958.

Marshall, Nancy H. The Night Before Christmas: A Descriptive Bibliography of Clement Clarke Moore’s Immortal Poem.

New Castle, DE: Oak Knoll Press, 2002.

Moore, Clement Clarke. Papers. Columbia University Library. New York.

Moore, Clement Clarke. Papers. Museum of the City of New York.

Moore, Clement Clarke. Papers. The New-York Historical Society.

Moore, Clement Clarke. Poems. New York: Bartlett & Welford, 1844.

Nickell, Joe. “The Case of the Christmas Poem.” Manuscripts, Fall 2002, 54;4:293-308

Nickell, Joe. “The Case of the Christmas Poem: Part 2.” Manuscripts, Winter 2003, 55;1:5-15.

Nissenbaum, Stephen. The Battle for Christmas: A Cultural History of America’s Most Cherished Holiday. New York: Vintage, 1996.

Oxford English Dictionary.

Patterson, Samuel White. “The Centenary of Clement Clarke Moore: Poet of Christmas Eve.” Historical Magazine of the

Episcopal Church. Vol. 32, no. 3, Sept 1963.

The Global Electronic Shakespeare Conference. www.shaksper.net.

Silver, Joel. Bookman’s Weekly. Dec. 23-30, 1996, 2153-54.

Sonne, Niels H. “The Night Before Christmas: Who Wrote It?” Historical Magazine of the Episcopal Church.

Vol. 41, no. 4, Dec. 1972.

Strong, George Templeton. Diary.

Tessier, [Alexandre Henri]. A Complete Treatise on Merinos and Other Sheep. Trans. New York: Economical School

Office, 1811. (New-York Historical Society copy)

Thomas, William S. Papers. The New-York Historical Society.

Tuttle, Norman. Letters. Museum of the City of New York.

West, Henry Litchfield. “Who Wrote ‘Twas the Night Before Christmas?’” The Bookman. Vol. LII, no. 4, Dec, 1920.

Appendix A: Clement C. Moore Handwriting Samples

Appendix B: “The Pig & The Rooster”

Below find a transcript of another poem by Moore.

The Pig & The Rooster

by Clement C. Moore (Poems, 1844)

(no date for this particular poem indicated)

The following piece of fun was occasioned by a subject for composition given to the boys of a grammar school attended by one of my sons – viz: “Which are to be preferred, the pleasures of a pig or a chicken?

On a warm sunny day, in the midst of July,

A lazy young pig lay stretched out in his sty,

Like some of his betters, most solemnly thinking

That the best things on earth are good eating and drinking.

At length, to get rid of the gnats and the flies,

He resolv’d, from his sweet meditations to rise;

And, to keep his skin pleasant, and pliant, and cool,

He plung’d him, forthwith, in the next muddy pool.

When, at last, he thought fit to arouse from his bath,

A conceited young rooster came just in his path:

A precious smart prig, full of vanity drest,

Who thought, of all creatures, himself far the best.

“Hey day! little grunter, why where in the world

Are you going so perfum’d, pomatum’d and curl’d?

Such delicate odors my senses assail,

And I see such a sly looking twist to your tail,

That you, sure, are intent on some elegant sporting;

Hurra! I believe, on my life, you are courting;

And that figure which moves with such exquisite grace,

Combin’d with the charms of that soft-smiling face,

In one who’s so neat and adorn’d with such art,

Cannot fail to secure the most obdurate heart.

And much joy do I wish you, both you and your wife,

For the prospect you have of a nice pleasant life.”

“Well, said, Master Dunghill,” cried Pig in a rage,

“You’re, doubtless, the prettiest beau of the age,

With those sweet modest eyes staring out of your head,

And those lumps of raw flesh, all so bloody and red.

Mighty graceful you look with those beautiful legs,

Like a squash or a pumpkin on two wooden pegs.

And you’ve special good reason your own life to vaunt,

And the pleasures of others with insult to taunt;

Among cackling fools, always clucking or crowing,

And looking up this way and that way, so knowing,

And strutting and swelling, or stretching a wing,

To make you admired by each silly thing;

And so full of your own precious self, all the time,

That you think common courtesy almost a crime;

As if all the world was on the look out

To see a young rooster go scratching about.”

Hereupon, a debate, like a whirlwind, arose,

Which seem’d fast approaching to bitings and blows;

‘Mid squeaking and grunting, Pig’s arguments flowing;

And Chick venting fury ‘twixt screaming and crowing.

At length to decide the affair, ‘twas agreed

That to counsellor Owl they should straightway proceed;

While each, in his conscience, no motive could show,

But the laudable wish to exult o’er his foe.

Other birds, of all feather, their vigils were keeping,

While Owl, in his nook, was most learnedly sleeping:

For, like a true sage, he preferred the dark night,

When engaged in his work, to the sun’s blessed light.

Each stated his plea, and the owl was required

To say whose condition should most be desired.

It seemed to the judge a strange cause to be put on,

To tell which was better, a fop or a glutton;

Yet, like a good lawyer, he kept a calm face,

And proceeded, by rule, to examine the case;

With both his round eyes gave a deep-meaning wink,

And, extending one talon, he set him to think.

In fine, with a face much inclin’d for a joke,

And a mock solemn accent, the counsellor spoke –

“’Twixt Rooster and Roaster, this cause to decide,

Would afford me, my friends, much professional pride.

Were each on the table serv’d up, and well dress’d,

I could easily tell which I fancied the best;’

But while both here before me, so lively I see,

This cause is, in truth, too important for me;

Without trouble, however, among human kind,

Many dealers in questions like this you may find,

Yet, one sober truth, ere we part, I would teach –

That the life you each lead is best fitted for each.

‘Tis the joy of a cockerel to strut and look big,

And to wallow in mire, is the bliss of a pig.

But, whose life is more pleasant, when viewed in itself,

Is a question had better be laid on the shelf,

Like many which puzzle deep reasoners’ brains,

And reward them with nothing but words for their pains.

So now, my good clients, I have been long awake,

And I pray you, in peace, your departure to take.

Let each one enjoy, with content, his own pleasure,

Nor attempt, by himself, other people to measure.”

Thus ended the strife, as does many a fight;

Each thought his foe wrong, and his own notions right.

Pig turn’d, with a grunt, to his mire anew,

And He-biddy, laughing, cried – Cock-a-doodle-doo.

[Note: The Museum of the City of New York holdings include several other examples of Moore’s anapestic poetry, much of it written for, or at the request of, his children. – SK]

Appendix C: Historical Timeline

1779 Clement Clarke Moore born.

1798 Moore graduates from Columbia College in New York.

1804 John Pintard founds the New-York Historical Society (NYHS).

1805-08 ca. Henry Livingston, Jr. supposedly writes “A Visit from St. Nicholas,” as per the memories of his children and grandchildren.

1809

Washington Irving publishes A History of New-York from the Beginning of the World to the End of the Dutch Dynasty by Dietrich Knickerbocker.

1810

John Pintard and the NYHS sponsor a St. Nicholas Day dinner on December 6th, celebrating the society’s “patron saint.”Accompanying the picture of the saint is a bilingual (Dutch-English) poem, beginning “Sancte Claus goed heylig man” (“Saint Nicholas good holy man”).

1813

First documented contact between Pintard and Moore. (NYHS has letters Moore wrote to Pintard in 1813 and 1818.)

Moore marries Catherine Elizabeth Taylor.

1819-20

Washington Irving publishes The Sketch Book of Geoffrey Crayon, Gent., which presents the American upper classes with a new (to them) image of Christmas cheer.

1821

General Theological Society re-established in New York City, with the help of John Pintard, Bishop Hobart, and Clement Moore. Moore begins teaching at the school.

Publication of the revised, second edition of Washington Irving’s Knickerbocker History.

Publication of antecedent poem “Old Santeclause.”

1822 Moore composes and reads “A Visit From St. Nicholas” to his children on Christmas Eve.

1823 “A Visit From St. Nicholas” published anonymously in the Troy, N.Y. Sentinel

1828 Henry Livingston, Jr. dies.

1829 The Troy Sentinel re-publishes the poem, providing a cryptic description of the author. (That description fits Moore, but not Livingston.)

1830 Death of Moore’s wife, Catherine.

1835 Formation of the St. Nicholas Society. Its goal, according to diarist and former New York City mayor Philip Hone, was “to promote social intercourse between native citizens,” meaning men of “respectable standing in society,” whose families had resided in New York for at least fifty years.

1837 First printed attribution of “A Visit From St. Nicholas” to Moore.

1844

Moore publishes his Poems, containing “A Visit From St. Nicholas.”

Norman Tuttle, former owner of the Troy Sentinel, corresponds with Moore regarding the original, 1823 publication of “A Visit.” His letter is written on the reverse of a broadside version of the poem containing Moore’s autograph corrections.

1853

[August] Moore writes out an autograph copy of “A Visit” (now in the Strong Museum).

1856 [March] Moore writes out a second autograph copy of “A Visit” for Oscar T. Keeler (now in the Huntington Library).

1860 Moore writes out a third autograph copy of “A Visit” (the Kaller copy).

1862

[13 March] Moore writes out a fourth autograph copy of “A Visit” for the NYHS, at the same time relating the early history of the poem.

1863 Moore dies in Newport, R.I., at the age of 84.

Appendix D: Early Publication Timeline

“A Visit from St. Nicholas” (“The Night Before Christmas”) was initially published anonymously, on December 23, 1823 in the Troy, N.Y.Sentinel. Over the next six years it ran in at least half a dozen newspapers – still anonymously. When Orville Holley, the Sentinel’s publisher reprinted it in 1829, however, he hinted at the author’s identity. The poet, the Sentinel announced, belonged “by birth and residence to the City of New York…he is a gentleman of more merit as a scholar and a writer than many of more noisy pretensions.” That description was well suited to Clement Clarke Moore, but not to Henry Livingston, Jr.

“A Visit” was first printed with Moore’s name in 1837 and, in 1844, Moore himself publicly acknowledged authorship when he included the piece in a compilation of his poetry. That same year, he corrected Holley’s reprint of the poem. Over the next two decades, Moore penned four autograph versions of “The Night Before Christmas,” in 1853 (now in the Strong Museum), 1856 (the Huntington Library), 1860 (the Kaller copy) and 1862 (New-York Historical Society). Each manuscript is unquestionably authentic.

Our list concludes with Harper’s 1863 printing of the poem (accompanied by a Thomas Nast illustration), which most likely elicited the first Livingston claim. Unlike the chain of evidence leading to Moore’s acknowledged authorship, there is no record supporting the contention that Henry Livingston, Jr. wrote “The Night Before Christmas.” In fact, there is no proof that Livingston himself ever claimed authorship, nor has any record ever been found – despite over 40 years of searches – of any printing of the poem with Livingston’s name attached to it. This list was compiled to show the ample opportunities that the Livingston family would have had to recognize the work both during their forebear’s lifetime (Henry Livingston, Jr. died in 1828) and immediately after Moore was credited as its author (beginning in 1837). Too, the roster of reputable editors and publishers (many of whom knew Moore personally) crediting the piece in their books and periodicals gives lie to the allegation that Moore could not plausibly have written the beloved Christmas poem. Not one of the editors who put their names and publications behind Moore’s authorship expressed surprise that a man of his character was the author.

Additional information on most of the following entries can be found in Nancy H. Marshall’s The Night Before Christmas: A Descriptive Bibliography of Clement Clarke Moore’s Immortal Poem (New Castle, DE: Oak Knoll Press, 2002). (Note: Items marked * are not on Marshall’s list, and several entries on Marshall’s list are not entered here.)

Appendix E: Joe Nickell Comparison of Phraseology

Phraseology and Imagery in “A Visit” Compared with Other Writings of Clement Moore.

By Dr. Joe Nickell, unpublished addendum to Manuscripts article, “The Case of the Christmas Poem.”

title: “A Visit from St. Nicholas” title: “From Saint Nicholas”

“’Twas the night before Christmas” “’Twas an autumnal morn, celestial bright”

adverbial all: “all through”; “all snug”; “dressed all in fur”; “all tarnish’d” adverbial all: “all ripe”; “all alone”; “all so bloody and red”; “in ice all clad”; “all white”; “all sweet and fair”

“all snug” “snug and tidy”

“Not a creature was stirring, not even a mouse” [From Hamlet: “not a mouse stirring”]

“The stockings were hung”; “And filled all the stockings”

“‘Your stocking quite empty’” [writes Saint Nicholas]

“visions of sugar-plums danced in their heads”

“visions rise”; “by visions flying around”; “this fleeting vision”

“And Mama in her ‘kerchief, and I in my cap” “a straggling kerchief, cap or book”

“Had just settled our brains for a long winter’s nap”

“a dreaming brain”; “Confounds my brain”; “raise a tumult in the coolest brains”; “rush wildly through my brain”; “dream-like images that fill my brain”

rhyme: “...a clatter, / ...matter” rhyme: “a clatter, / ...spatter”

“Away to the window I flew like a flash” “Down with the windows, run, here comes the gust / Quick, quick...See! what a flash!”; “in flashes bright”

“The moon on the breast of the new-fallen snow, / Gave the lustre of mid-day to objects below” “As beautiful a moonlight as ever shone”; “All objects shone so lucid and so clear”; “The silent snow has clad the ground”; “the varied scenes below”

“what to my wondering eyes should appear”

“with wonder”; “An object, sudden, meets my eye”; “the wond’ring giddy crowd”

“a miniature sleigh, and eight tiny rein-deer” [From The Children’s Friend: “Old Santeclaus with much delight / His reindeer drives this frosty night”]

“More rapid than eagles his coursers they came”; “the coursers they flew”

“high-bred coursers”; “her rapid course”; “rapid motion, as the carriage flies”; “Away they flew...

“Now, Dasher!”; “Now dash away! dash “away! Dash away all!”

they dash about”; “In steamboats dashing”; “dash’d with pain”; “that’s dash’d” “But swift, away, away...”; “to bed away”; “the drivers...dash over ruts and stones”

“now, Dancer!” “that dance upon air”

“now, Prancer!; “The prancing and pawing of each little hoof” “And prancing steeds”

“On Comet!”

“on Cupid!”

“the meteors blaze”

“And write of Cupids”; “the wonder Cupid wrought”

“on, Doner and Blitzen!” [i.e., after the German for Thunder and Lightning]

“See! what a flash!...and thunder, crash on crash”; personification: “Thunderer”

“mount to the sky” “mounts in spirit to the skies”

“the sleigh full of Toys, and St. Nicholas too.”

“‘I will leave you...some toys’” [writes Saint Nicholas]

“His eyes - how they twinkled! his dimples how merry! / His cheeks were like roses, his nose like a cherry!” “twinkle of the eye”; “The rosy cheeks, the dimpled smile”; “With sparkling eye, with rosy cheek”; “his snub-nose”

“droll little mouth” “droll remarks”

“the smoke it encircled his head like a wreath”; “a right jolly old elf”

“a wreathed mist”; “The fairy scene”; “By fairies”; “a sprite”; “wood-nymphs”

“in spite of myself” “in spite of reason”

“A wink of his eye” “gave a deep-meaning wink”

“nothing to dread” “secret dread”; “dreadful fate”

“And laying his finger aside of his nose”

[From Washington Irving: “laying his finger beside his nose”]

“ere he drove out of sight”

“ere long”; “ere retiring to their welcome rest”; “vanish’d from my sight”

“to all a good night’” [says St. Nicholas] “‘I must bid you good bye’” [writes Saint Nicholas]

|

was an professor at Columbia College, now Columbia University who donated land for the foundation of the General Theological Seminary. He is the author of the yuletide poem "A Visit from St. Nicholas."

Authorship: A Visit from St. Nicholas

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.